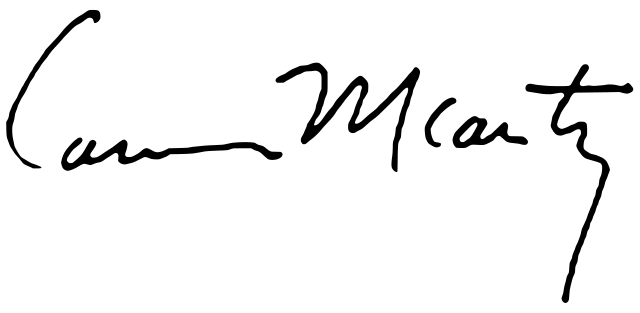

I am reading Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger, burning through it like I have a deadline. Again, I marvel at his skill with dialog and moody character. Again, I rage at his refusal to use quotation marks. Why, Cormac? Why do you and so many other so-called “literary fiction” writers opt not to use proper punctuation? The answer I expect these writers would want me to settle on is “genius,” but I believe it’s really “affectation.”

Quotation marks are, among their other roles, used to “enclose a person's spoken words or unspoken thoughts.” (Rules for Writers by Diana Hacker). End of story, right? Seeking confirmation, I opened The Elements of Style, Fourth Edition. Elements showed me how to use quote marks, etc., but did not dictate when to use them.

It did say,“Prefer the standard to the offbeat” (Page 81), which I’m taking to mean ‘don’t get clever just for the sake of looking smart.

James Joyce, in his autobiographical novel A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, used the long dash instead of the lowly quotation mark. It's something he apparently borrowed from the French -- an affectation by an Irish lad who wanted to make himself seem fancy.

Kaye Gibbons — lauded by talk-show magnate Oprah Winfrey, The New York Times Book Review and others — did not use a single quotation mark in her 1987 book Ellen Foster, nor in the 2006 follow up The Life All Around Me by Ellen Foster.

In a 2008 article for the Wall Street Journal, author Lionel Shriver said abandoning quotation is a sign that literature is becoming pretentious and less approachable: “Some rogue must have issued a memo, 'Psst! Cool writers don't use quotes in dialogue anymore' to authors as disparate as Junot Díaz, James Frey, Evan S. Connell, J.M. Coetzee, Ward Just, Kent Haruf, Nadine Gordimer, José Saramago, Dale Peck, James Salter, Louis Begley and William Vollmann.” (“Missing the Mark,” WSJ, Oct. 25, 2008)

Shriver writes that the reason behind the banishment of quotation marks is an attempt at “a minimalism that lends text a subtlety and sophistication.” However, the result, he believes, is to leave popular fiction, which still uses quotation marks, more attractive to readers, and literary fiction as an ever-more dusty slog up a difficult road.

“To the degree that this device contributes to the broader popular perception that 'literature' is pretentious, faddish, vague, eventless, effortful, and suffocatingly interior, quotation marks may not be quite as tiny as they appear on the page.” (“Missing the Mark,” WSJ, Oct. 25, 2008)

Shriver goes on to say the practice creates confusion between the characters’ interior and exterior lives as “when the exterior is put on a par with the interior, everything becomes interior. … When thinking, speaking and describing all blend together, the textual tone levels to a drone. The drama seems to be melting.” (“Missing the Mark,” WSJ, Oct. 25, 2008)

This blend or creation of the drone may be the point of some of this. Frank McCourt did not employ quotation marks in his memoirs ‘Tis, Angela’s Ashes, and Teacher Man, and the decision enhances a narrative that is clearly part of a past dusty and dim even to the writer. When Joyce Maynard does it in Labor Day, there’s a similar feel, that of a character looking back to a not-quite clearly remembered history. If, as in journalism, quote marks are used to delineate the exact speech that a source utters, is there a need for them if the dialogue is only half remembered, its blanks filled in through context clues, and only heard at the distance of years?

Cormac McCarthy’s The Road also has a feeling and tone of things gone past and only vaguely recalled. The dialogue is more paraphrased than precisely captured.

He cried for a long time. I’ll talk to you every day, he whispered. And I won’t forget. No matter what. Then he turned and walked back out to the road. (The Road, page 286)

I thought I might be onto something but when, several summers ago, I asked Joyce Maynard about her quotation-mark aversion in Labor Day, her answer boiled down to aesthetics; she likes the way the page looks without them. When Oprah Winfrey asked McCarthy about his punctuation peculiarity, his answer was similar: “You shouldn't block the page up with weird little marks. If you write properly, you shouldn't have to punctuate." But, at the same time, "You really have to be aware that there are no quotation marks to guide people, and write in such a way that it won't be confusing as to who is speaking." (Flak Magazine, June 18, 2007)

So, no plan. Just prettiness. An affectation. The abandonment of quotation marks speaks more of the author’s desire to look “literary” than of the needs of the work. Misuse of them, or their abandonment, shows me a writer who thinks he or she is too cool for school.

But I’m still reading Cormac McCarthy.

NEWS: I attended the Boskone Science Fiction & Fantasy Convention this past weekend, and the high point was signing a copy of Mercury Rising for a real live astronaut. It was pretty cool. I may have geeked out a little. I sort of thrust the book upon her in panic, and she was groovy enough not to recoil.

The second and final book in the First Planets duology, Earth Retrograde, will be out in October 2023.

It has been many years since I have read McCarthy and can't say I noticed, which probably says more about my attention than the writer's skill or affectation. I am not a great reader of 'literary fiction' so can't comment on any others. I will say it is harder reading those type of books and not in a sense that they are stretching me or challenging, but just dry, dusty and often boring. The words do not seem transport or elevate but rather sit there and have to chewed upon as if I am some ruminant grazing the page. Thanks for reminding me to go read McCarthy, I understand some new work was published this year or last year.